Recently I circulated a Views titled “The ‘Path-to-Purchase’ is Often a U-Turn.” In order to get the full value of this issue, you should be familiar with the content of that issue. (Others, such as “The Misguided Bobbing of the Long Tail,” would also be very helpful.)

The objective facts are that there are a few retailers who obtain outsize sales and profits in comparison to other stores carrying similar merchandise. Because these few have some obvious differences from the thousand-store chains, many retailers ignore the underlying principles that drive the outsize success of these super performers. Here it is my intention to explain the relevance of these super performers to all retailers, and how to leverage the principles that drive their success, without upending your own operations. That is, where they may be selling five times as much (500% more sales than you,) you don’t have to go the whole way with their business model and merchandising strategy to maybe get a 50% increase in sales yourself.

The fundamental reason these super performers get the results they do is because they make effective use of the 80% of shopper time that is wasted in typical retail stores. Think of it this way: In just about any type of store, but especially supermarkets, the “typical” shopper comes through the door looking to buy 3 to 10 items. The problem they face with 20,000 to 100,000 items scattered across a large sales floor is two-fold – where in the store are the items I’m interested in; and, when I get to where they are, how will I know which one of the hundreds offered I should buy? These two problems (twin time wasters) can be summarized as navigation and choice. However, these two also represent huge opportunities.

You can make massive improvements of these two problems/opportunities by two simple expedients:

- Tell the shopper where to go!!!

- Tell the shopper which to buy!!!

These may seem like revolutionary ideas to you, but they are based on solid shopper science.

The Opportunity and Challenge of Self-Service

Before self-service retailing was common, retailers personally, or through staff, mediated all sales to the shopper, with no need to tell them where to go, and telling them which to buy was mixed into the shopper/staff interaction. This is not very efficient, and the advent of mass production and mass distribution, to mass markets, provided massive advances in efficiency for everyone involved: shoppers, retailers and their suppliers. This led to the past 100 years being dominated by self-service retail. The future will also be dominated by self-service retail. But something more than the old “pile it high, and let it fly,” plan of the self-service retailer is needed. Pile it high; let it fly, is an anti-“tell’em where to go; tell-em which to buy” selling strategy. The first is passive in nature, and the second is active. Hence, my continuing observation that retailers are too passive, and that active retailing is the wave of the future.

Technology has some solutions relevant here, but it will be some time before everyone will be fully engaged with those solutions. You need the profits NOW! And the reality is that the program I’m outlining here will only be further accelerated by technology, by and by.

Telling Shoppers Where to Go

So let’s return to the problem of your shoppers coming in your door, and buying maybe five items out of 40,000 you have available. Just remember that the shopper is more skillful at eliminating 39,995 of those items than they are at finding the five they want. That is, they have a powerful subconscious filtering system that simply ignores or discards vast amounts of what you are offering. But you should know that “The ‘Path-to-Purchase’ is Often a U-Turn.” So if you are really going to understand and work with your shoppers, you should make a prominent and logical U-Turn in your store that takes them from the door to checkout on a path that you can be an expert on, and can work with them on.

That’s right, the only way for you to really engage with your shoppers is to stop trying to get them to spread all over your store in the hopes that they will find something to buy. Rather, gently guide them on your selected, preferred path for them.

We’re dealing here with the first requirement mentioned above: “Tell the shopper where to go!!!” You may think, “won’t they be offended if I tell them where to go?” And what about all the rest of the places I would like them to go? We’ll discuss how the super performers do this soon, but just be aware that retailers all over the world are obstinately refusing to help shoppers buy a lot more from their stores, instead insisting that the shopper respond to obsolete ideas about store design and merchandising. Every super performer does tell people where to go and which to buy, but in gentle and subtle and effective ways.

I’m telling you that you should tell them to go on a U-turn in your stores, first and foremost because that is their natural tendency, anyway. And secondly, it is so that you can begin to plan and strategize how to sell to them on that specified U-turn. The U-turn is the grand-daddy of all shopping trips, the true archetypal shopping trip.

Most of the deficiencies in retailing arise because retailers are faced with managing overwhelming options, just as the shopper is similarly overwhelmed. The first of those overwhelming options is the multitude of optional ways of navigating the store – literally millions of possibilities, even in a quite small store. The super performers sometimes still have a multitude of options, but they have created one dominant pathway. Hint: It’s a lot easier to manage ONE than millions.

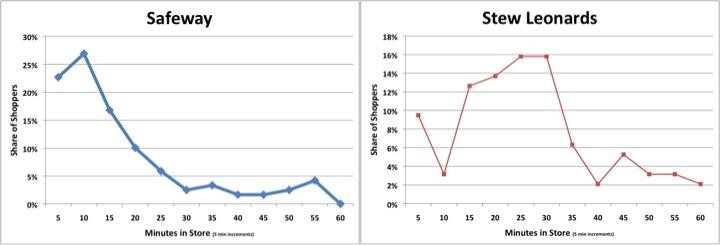

Look at the impact on shoppers’ trips, comparing a store with diffuse paths (Safeway,) with one with a single “U-turn-type” path (Stew Leonard’s.)

The Safeway store here is the typical multi-aisle store, with a nearly unlimited number of path possibilities. The U-turn is the most common form of trip, even at Safeway, but the U-turn is diffused across multiple aisles in this store. Most of the shopping trips here are in the 5-20 minutes range, with a rapid fall-off from the peak 10 minute trip. Stores of this type typically manage to achieve $15-30 million in annual sales. The Stew Leonards store, on the other hand, has few very short trips – 10 minutes or less, with large numbers of shoppers in the 15-30 minute range, mostly similar trip lengths, because of the single path for all shoppers. Stew Leonard’s stores typically deliver $100 million in sales. Remember that 80% of shopper time wasted or “lost” in the typical store? Not at Stew Leonard’s. Some substantial portion of that time is recovered and converted to purchasing instead of worthless (to the retailer) and frustrating (to the shopper,) time spent wandering about the store. See the Wharton publication, “The Traveling Salesman Goes Shopping.”

Before we move on to telling the shopper which to buy, we should note that there could be more archetypal trips in a store than just the U-turn. (We’ve already noted multiple U-turns.) Having said this, we have attempted to discern other archetypal paths in drug stores, with no real success. The reason, in retrospect, for not being able to find other archetypal trips is that the store was designed to deliberately spread traffic across the store. We have found this strategy elsewhere, and have found stores with the most uniform traffic across the typical multi-aisled stores, are also anecdotally the poorest performing in terms of total store sales.

Telling Shoppers Which to Buy

I would NEVER tell shoppers to buy something they are not already predisposed to buy. Way too much retailing is really desperate hectoring of shoppers, hoping they will buy something more. Suppliers have literally millions of items they would like to sell. But as we noted, shoppers have a massive filter in place to ignore the vast majority of what is in the store. It’s a matter of shopper-survival.

How do you know what they want to buy? How about checking what they are already buying? I’m not talking about loyalty cards and one-on-one merchandising, but selling to the crowd. Just as the U-turn is a good representation of “the crowd,” so “the crowd” quietly announces exactly what they want to buy in each store. How so? Check the transaction log, listing all the individual shoppers, and their individual purchases, item by item sales per shopper, every day, week or quarter. There really are only a few hundred, of the tens of thousands of items, which are actually making an outsize contribution to store sales. That’s because those few hundred items are what the shoppers are telling you, “This is the stuff we mostly want to buy.”

SO . . . How about telling “the crowd,” this is the stuff YOU probably want to buy? This is my conception of “social marketing,” and it works very well. Let’s face it, no matter the class of merchandise (automobiles or toothpaste,) shoppers are reassured and comforted to know that they are buying the top selling item. After all, there is something to “The Wisdom of Crowds,” (James Surowiecki.) When millions of people, or all the shoppers in your store, choose a particular item far more often than all other items, it is probably the best choice for me and you, too. In each category, subcategory or brand, one item and only one item is the winner – and that is the only item (or a few) you need to tell the crowd of shoppers to buy. It doesn’t mean that you eliminate all or any of the others. All those others are very attractive at getting shoppers into the store (and some people really, really want something other than the winner.)

But retailers all over the world are cutting their own throats by simply refusing to help the average shopper just get their stuff and get the heck out of here. Stop playing games!!! Tell them which ones are the winners NOW, and start reaping additional sales and profits NOW! End the “treasure hunt” as a justification for what is really substandard retailing, even if it is received wisdom and practice by most of your competitors.

The Super Performers

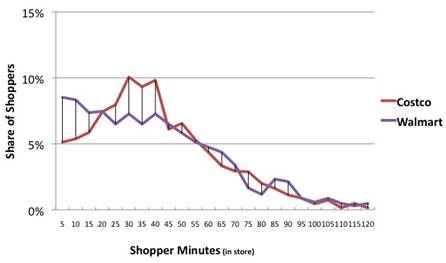

Rather than going into more detail on paths and products, and more on how to “tell” the shopper, let’s illustrate how super performers tell shoppers where to go, and which to buy, and continue our comparisons to more conventional retailers. Beginning with Walmart and Costco:

Both of these retailers have a broad array of merchandise, across consumer electronics, clothing, furniture and household items, pharmacy, food, automotive, etc. Here we see that both retailers have much longer trips than the grocers discussed above. But most noteworthy is that Costco trips are dominated by the 30-45 minute cohort, just as Stew Leonards is by their 15-30 minute cohort. Stew Leonards, you may recall, has the constrained serpentine path so that all shoppers essentially execute the same path, which leads to this clustering of trip lengths. So this similar clustering of Costco trip lengths suggests that maybe clustering of trip paths into a U-turn is going on here, too. In fact, this particular Costco hits sales of a million dollars, per day, often enough to achieve $270 million per year in sales, according to Jim Sinegal, founder and CEO. (This is more than twice the typical Costco at $125 million in annual sales.

It is interesting that both the Costco and the Stew Leonards essentially adhere to the U-turn type of store. For Stew Leonards, it is a single entry into a serpentine path leading to a single exit into the general checkout area. Topologically, this is identical to a U-turn. Think of it as a wiggly U-turn. But for the shopper it IS effectively doing a U-turn path. For the Costco store the entry leads into a broad aisle that moves to the back of the store, across the back, and returns to the front.

This photo shows the interior of one store:

The entry is behind the camera, with the wide, main aisle moving slightly to the left of the large home electronics department on the right. Notice on the right, beyond home electronics are tall “warehouse” racks with merchandise displayed on the lower level and storage above. The path of the U-turn moves past those warehouse displays on the right to the rear of the store, and then crosses that large central open area, and past the food at the rear, and then returns to the front just this side of the tall, warehouse displays on the opposite side of the store.

This is a very important design which I refer to as the inverted perimeter. Think of your typical supermarket as a perimeter design, where the wide U-turn moves around the perimeter of the store, with those visually blocked “warehouse” aisles crowded into the middle of the store – “steel canyon” center-of-store aisles. Inverting this as Costco has done means that all of the best selling, most profitable merchandise (the Big Head,) can line the wide aisle, and at the same time the total store (the Long Tail) stays visible to most of the shoppers in the store, most of the time.

This visual availability is a HUGE issue. For the shopper, if you can’t see it, it’s not there. So the inverted perimeter gives ample exposure to the big head, without hiding (or compromising) the long tail. That is, instead of trying to get shoppers to come to the merchandise, Costco puts the high volume merchandise into the path that shoppers will almost certainly pass. This is Costco’s way of telling the shopper which to buy. Stew Leonards does the same thing, by only having a single path. But Costco is able to carry a much larger selection of merchandise (big selection = more attractive) but doesn’t let it get in the way of selling the popular stuff. This is done with all those warehouse racks that ascend to the heavens around the perimeter. (This same conceptual design is beginning to be used very effectively by CVS drug stores, and a number of other retailers have tested or are moving in this direction.)

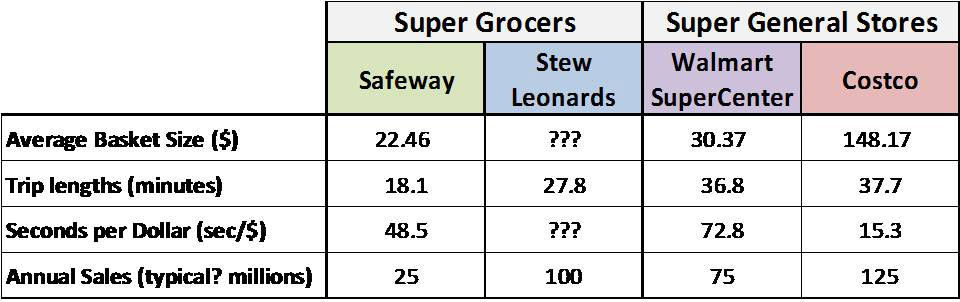

We have shown before that the faster you sell, the more you will sell. (“Shopper Efficiency vs. Total Store Sales”) We are now showing the impact of selling speed on a wider variety of stores, including those discussed here. The results are striking:

These numbers show us that Walmart and Costco have very similar “average” trip lengths, with radically different basket sizes – Costco having something like 5X the basket size as the Walmart SuperCenter. Both stores are very large in floor space, but the Walmart is carrying two very heavy disadvantages:

-

The winning, top selling items are buried in an indiscriminate sea of options, maybe 100,000 SKUs. Indiscriminate, because there is nothing telling shoppers which items are the ones they are most likely to need – based on the purchases of the rest of the shoppers.

-

For the few items most shoppers will want to buy, there is NO clear path that connects those products. There is no clear U-turn, creating the typical “treasure hunt” model common amongst retailers, who comfort themselves that shoppers enjoy this frustration.

The result is that with similarly broad category lines of the two stores, Costco manages to sell a dollars worth of merchandise in a scant 15 seconds. The same dollar’s worth of merchandise takes the Walmart Super Center 73 seconds, nearly five times as long. Once again confirming that the faster you sell, the more you will sell. This is Sorensen’s first principle of retail selling, and more confirmation of the principle is accruing regularly.

We don’t have basket totals for Stew Leonards, but do note that with a 50% increase in average trip length (and probably a lot less traffic,) Stew Leonard’s outsells Safeway by 4-5 to 1. Safeway is struggling under the same two disadvantages as Walmart – and the rest of the retailers operating on the same basic principles.

I should point out, though, that NONE of the four stores do a particularly exemplary job of “telling the shopper which to buy.” In both the Stew Leonards and Costco examples, those stores have greatly reduced SKU counts compared to the Safeway and Walmart stores, and only increase their focus on top sellers by simply not carrying as many of the long tail. It is important to note here that it is NOT the reduced SKU count that sells more, per se, it is the FOCUS on the top sellers which is virtually forced by the reduced SKU count. In a sense, Stew Leonards and Costco are “Big Head” stores, like Lidl, Aldi and Trader Joe’s. The others are “Long Tail” stores, with vast and very attractive merchandise selections. (Attraction and selling are two VERY different functions.) If “Long Tail” stores would properly emphasize and focus on their own “Big Heads,” by telling the shopper to buy the big head, they should outperform those “Big Head-only” stores. This would require an item focus, item management, if you will, which can be done as an overlay on the widely used category management. Category management was a great advance when it was introduced 20 years ago, but when allowed to preclude item management, it becomes an albatross around everyone’s necks: shoppers, retailers and brands.

Although I have said that the big head stores are not really conceptually telling shoppers which to buy, they are doing this to an extent, particularly by explicitly endorsing item management. Some quotes:

“Well, we have never been a category company – that was decided long before I came . . . We look at it item by item. That doesn’t mean we don’t have a fair representation with a category. But usually it’s only the top five or six items in that category, and we look at them as items!” “So our traffic is up, our sales are up. We’re in the 3% range right now over last year” - Charlie Burnett, COSTCO

“If an item doesn't pull its weight in our stores, it goes away to gangway for something else.” – Trader Joe’s

“What's not to like? They're very good retailers [Trader Joe’s], and we admire them a lot.” - Jim Sinegal, co-founder CEO, COSTCO

Having a wide selection may help get customers in the store, but it won't increase the chances they'll buy. “It [wide selection] takes them out of the purchasing process and puts them into a decision-making process,” explains Stew Leonard Jr., CEO of grocer Stew Leonard's, which also subscribes to the ‘less is more’ mantra. [From the Fortune article on Trader Joe’s, linked above.]

Again, “less is more” only if you refuse to focus on, and tell the shoppers to buy the less, in the presence of the more. And that’s all I have to say about that – at least for now.