This issue of the Views provides further insight on how and why you can use the dominant path through the store to increase sales. Ten years ago I articulated "The Holy Grail of Retailing:"

- To know exactly what each shopper wants, or may buy, as they come through the door of the store, and...

- To deliver that to them right away, taking their money and speeding them on their way.

So we want to focus here first on "what each shopper wants, or may buy," and will use an expanded view/definition of the "shopping list" to encompass exactly this – what the shopper wants or may buy. It is a mistake to limit this "shopping list" to a piece of paper or other overt evidence of a shopping plan. In fact, with a better understanding of the role of habit (or the subconscious mind) in shopping, the "wants or may" abbreviates what Neale Martin refers to as the executive mind (wants) or habitual mind (may.) (See Neale Martin, Habit: The 95% of Behavior Marketers Ignore.)

First, let's deal with the fact that shoppers widely report that they use a shopping list, when in fact they do NOT! This became obvious over the years as we interviewed shoppers, in the store, about their shopping practices, and the number of shoppers that solemnly assured us that they always shop with a list. But when asked to see their list, it's "Oh, I guess I left it at home today – or I must have dropped it – or 'you fill in the blank'."

The reality is that, based on observation of supermarket shoppers, only about one fourth of them use an explicit shopping list – paper or electronic. But let's not be so hasty in dismissing then the idea that they did not have a list, and, other than a mental list, I suggest something else:

Most shoppers are familiar with the stores they are shopping in regularly, and most shoppers only buy 150-200 different items regularly – out of a store with probably 40,000 items. In fact, individual shoppers habitually follow a similar path week after week for similar shopping missions. Given the speed with which individual purchases are made, often only a second – or a few – it is obvious that no serious mental energy is going into the purchase. This means that their habitual, subconscious mind is simply playing out a script in the acquisition. If this is so, and I believe that it is, then the script is being triggered by what they sense (see,) on displays. Another way of putting this is that their "shopping list" actually consists of a series of triggers occurring on their usual path through the store. In this way, each shopper builds up, over time, a handy file of "shopping lists" for trips with various purposes.

Since I am not prepared to scientifically prove this concept, presently, I'll call this the store-based shopping list hypothesis or path list hypothesis, for short. Whether it is true in all particulars, at the least it accounts for a great deal of shopping behavior (purchases) and points the way to increased sales for the retailer – and increased satisfaction and ease for the shopper.

Of course the path list explains the shoppers belief that they always shop with a list, since in this new sense, they do. Further, the number of items needing remembering on any given shopping trip is often shockingly small:

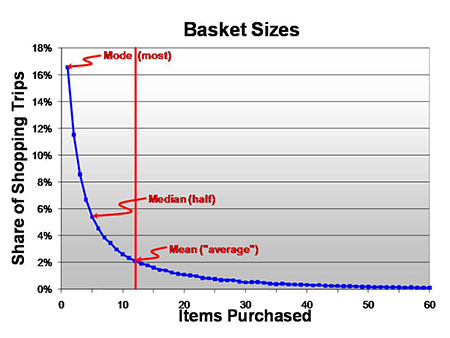

Notice that the most common number of items purchased in a supermarket is one, with half of all trips buying 5 or fewer items. This means that a subconscious shopping list doesn't need to be very long. Couple this with the fact that most regular shoppers are in a store at least weekly – if not more often. The significance of this is that ordinarily, should the path list fail to achieve the purchase of some needed item, there will be opportunities to correct the lapse, soon, on a subsequent trip.

Now that we have a better idea of the nature of the "shopping list," if we are to sell to it, we need to inquire as to just what specific items are on it. Is this feasible, given the tens of thousands of shoppers who may visit the store? For sure!

We noted above that most shoppers have a basic list of 150-200 items that they purchase habitually. However, there is a second 150-200 items that they buy only occasionally – special occasions, holidays, etc. Now we introduce another very important concept that we have seen confirmed repeatedly: If you drop any 10,000 shoppers into a store, and observe exactly what each individual does, you will get an image of the behavior of the crowd. Now, if you drop any other 10,000 shoppers into any similar store, you will get nearly the identical image. We might call this the constancy of the crowd. Further, I will suggest that if you are a retailer or brand supplier, it is far more important to understand the crowd than segments or individuals in it. (There are vast fortunes to be made by the simple expedient of shifting to this perspective.)

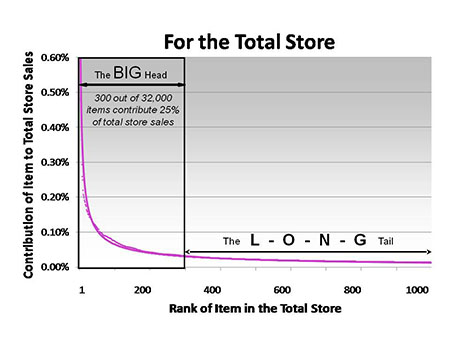

So what is the result of layering tens of thousands of shoppers with short shopping lists, 150-200 regular items; plus 150-200 occasional items? Here it is:

It's no wonder that 300 items out of tens of thousands contribute 25% of the total store sales. It is simply a matter of fact that the shoppers in the crowd all have a strong tendency to buy what the rest of the crowd does, and they all do it over and over again. So, individual shopping lists begin to coalesce around a fairly constant set of merchandise. Hence – "The Big Head!"

It is important to recognize that the big head derives from the hearts and souls of shoppers, reflecting as it does the most essential items of their lives. This, in turn, brings the focus to individual items NOT categories. Bear in mind that the whole scheme of organizing individual items into groups, whether called categories, departments, or whatever, is NOT driven by shopper needs or requirements. It is in this sense that category management largely addresses the needs of retailers and their suppliers, and very nearly ignores the shopping crowd. Shoppers have been "trained" to adjust to what is mostly operating convenience for retailers. Again, I am not going to address here the scope and details of what has become the kluge of modern self-service retailing. Category management is a response to the need to manage tens of thousands of SKUs in the modern self-service warehouse, aka supermarket, supercenter, hypermarket or other self-service store.

Shoppers, on the other hand, never buy categories, but only individual items. A shopper in the aisle is essentially faced with the mayhem of a gladiatorial contest of brand against brand, with the careless Caesar-retailer accepting the tribute of all contestants. The delusional presumption that this is a shopper focused arena is farcical – with occasional exceptions, some of which I have detailed in earlier issues of the Views. I will clarify this comment in a discussion below on carbonated soft drinks.

So... Just what are those big head items? For supermarkets, usually bananas or 2% milk are at the head of the list. In fact, the top of the list is crowded by produce items. This is at least partially due to the fact that there is minimum "SKU" proliferation in produce. (Actually, PLUs, "Price Look-Ups" instead of SKUs.) This means that bananas face no competition with other bananas, typically. Any competition they face is more likely with apples, pears, grapes, etc. And even though some of these do have significant varietal selections, it doesn't begin to approach the massive confusion of soft drinks, cereals or frozen foods.

Probably the dominant characteristic of personal selling, as contrasted with self-service buying is that a seller focuses the offer on a single item as quickly as possible, the one the customer will buy. (Of course, squeezing out options at what seems an acceptable and reasonable rate to the customer.) Clarity and distinction of single items is the single most important component of SELLING!!! It is NOT the price, the selection, the brand or anything else. If you want to sell something to someone, the most important thing you can do is tell them to buy specifically THIS!!! Shoppers can't buy generalizations, groups, etc.

Bananas then are the top-selling item in supermarkets simply because they have no real competition in these self-service environments. You either want bananas, or you don't. Wham, bam, the decision is made. (Of course, if you don't like them, or they're too green, these factors can enter in.) But there is another point to be made from the top selling bananas. Obviously they ring the bell for a lot of people, over and over. But the reality is that almost certainly a lot more of them could be sold. First, the general principle here is that management tends to not spend a lot of time worrying about things that are going well – like the selling of bananas. Management is instead going to look for things that are NOT going well, and attempt to fix those things (Management by Exception.) It's inherent to our natures, but does not address maximizing performance of the organization, at large.

Second, for an example of what this means in terms of bananas, when an associate of mine became aware of the facts about bananas, his response was, "Really? I love bananas, but don't eat them very often." Turns out that his wife buys them regularly, but before he ever gets a chance to eat one, the kids have eaten them all! How many times do you think this situation repeats itself around the world? And for many other top selling items.

The point is that the top selling items are always the ones most amenable to large increases in sales. Why? Because shoppers are shouting loudly, if you will listen, THIS IS THE ITEM WE WANT AND NEED!!!

As we move our way down the list of items in the big head, we notice large representation near the top of the list, of all things beverage. This includes 2% milk, (which often outsells bananas,) sodas (Coke and Pepsi,) with waters, Red Bull, etc. This is a manifestation of the Maslow principle, in terms of physical needs: you can live –

- A few minutes without refreshing your air supply,

- A few days without refreshing your liquid (beverage) supply,

- And a few weeks without replenishing your food supply.

- Everything else is truly non-essential, including clothing, housing and transportation.

So, using this basic physiological scheme it is readily understandable that beverages would dominate the top of shoppers' expressed needs and wants, their path lists as reflected in the log of individual shoppers' purchases.

Of course in a grocery store one would expect to see food high on the list, but it is noteworthy that foods for immediate consumption, and snacking are especially high on the list.

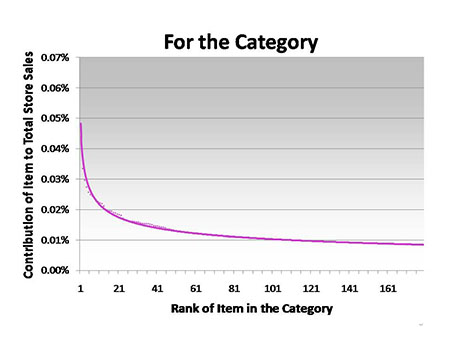

These principles relating to sales of the whole store, can also help us understand categories and brands. The path shopping list for a category (frozen food) looks like this:

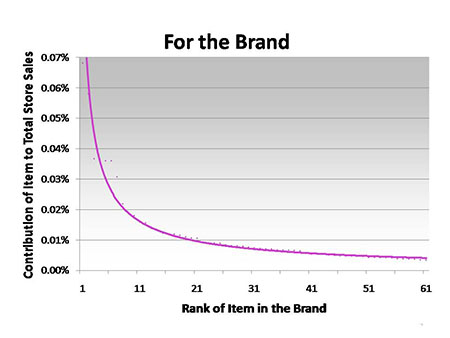

And for a brand (Coke):

So even for a brand, the Big Head/Long Tail paradigm prevails, with a top few items delivering the lion's share of the sales.

The path list hypothesis explains all this behavior, but even if the explanation is inadequate, the facts are not: the way to achieve large increases in sales is to simply "peek" at all the shoppers' lists, and make it easy and fast for them to acquire what they want. Focus on, and sell, a lot more of the few that are already selling well.

Now to the in-aisle gladiatorial contest mentioned above: the business realities of the store virtually require this brand-on-brand and item-on-item contest. What happens there, relative to the shopper, is less troubling than what does NOT happen there: genuine selling to the shopper, rather than just hoping the shopper buys something. We have dealt with this in several past issues of the Views, and will return to the subject soon.

Other than just calling attention to the serious contention in the aisle, I want to cite three necessities that justify it:

- No matter how large the store, shelf space is always limited, in relation to products available to put on them. Since there are well over a million different items waiting on manufacturer's warehouse shelves, to be sold to shoppers, even a store with 50,000 different items is turning away a lot of possibilities. This means competition for shelf space virtually has to be fierce. Moreover, it is not just a matter of getting an item represented in the store, but the number of facings that a brand manufacturer can assume some control over is crucial. For a brand, every facing they don't control, a competitor will control. And no retailer is going to give brands discretionary access to a large space to do with as the brand judges best. So SKU proliferation is the cutting edge tool to gain more facings. A line that includes 20 items, well distributed, supported with advertising, and ostensibly supported by consumer research, will justify more facings on the shelves than will one with 12 items. And from just the brute force of larger presence, the 20 item line may do better than a superior 12 item line, that just can't get the exposure on the shelf. SKU proliferation is a competitive imperative.

- Secondly, observers often overlook that stores ARE warehouses, where merchandise is made available for stock-pickers, known in self-service as shoppers, remove items from the shelf. The industry has addressed the resulting problem of out-of-stocks (OOS) when shoppers have purchased all the inventory on the shelf, and must switch items, substitute, or simply avoid purchasing. Studies have shown OOS to result in something like 8% of lost sales across the industry. I have often said that retailers and brands should thank God for out-of-stocks, because it means that something is selling here. Hot stores selling lots of merchandise fast are racing to refill shelves, sometimes simply working at breakneck speed to keep up with the shoppers. (I have seen two supermarkets in my life that were running flat-out to try to keep up with the shoppers.) These situations are at least partially buffered by having a larger amount of inventory on the shelves, so brand suppliers with greater allocation of shelf space have more protection from OOS.

- The third reason militating SKU proliferation is that the wider the selection of merchandise in a store, the more attractive that store is to shoppers. There is a crucial distinction here between attracting shoppers, and selling to them. Shoppers are very pleased to shop in a store that has 100 times more items in it, than they themselves will want to purchase. This is the primary role of "the long tail." Not to make sales, but to attract shoppers. The problem is when the long tail so dilutes and hides "the big head" that it suppresses sales of the top sellers by slowing shoppers down, in their quest for just the few items they want. Since warehousemen/retailers do not have to do all the stock-picking that the self-service shopper does, they are oblivious to the serious damage they do to their own businesses by failing to expedite the shopping process.

With this last reference to "the stock-picking that the self-service shopper does," we return our focus to the shopping list, which is essentially the stock-picker's prescription for what to remove from the warehouse-retail store. (They ARE all warehouses, after all. :-)) The number one failure of self-service retailing is not a failure to select and stock the right merchandise, it is a failure to make a distinction between the big head and the long tail, in the misguided hope that by slowing the shoppers, perhaps one more long tail item can be sold. Instead, the key is to accelerate the focus on, and speed of selling, of the big head, so that the shopper has plenty of (pleasantly surprised) time to buy one or a few more items. He that hath ears to hear, let him hear!